"We Can't Change The Past, But We Can Change What It Means To Us"

JEWS OF THE UNIVERSE: Introducing Dara Horn

“My mother has a PhD in Jewish studies, so Judaism was something that was always important in my family, and it was coming through the channel of education. I never went to a Jewish school; I went to public non-sectarian schools. But I did everything else. I was the only one who learned Hebrew in congregational Hebrew school.

In New York City, JTS used to have a program for teenagers. Rabbinical students were teaching these classes on weekends, so it was an extra day of study, focused on Jewish texts. It was four or five hours on Sundays, and I’d come in and out of the city from New Jersey for those.

Then also, as a teenager, I made an independent decision to study Hebrew more intensively than I could at the rate of just once a week. I signed myself up for an adult education class at the local JCC that gave me four more hours a week, during weeknights. I didn’t realize that, at the age of 15, I would be the youngest student in the class by at least a couple of decades. They called me tinoket, which means “baby girl” in Hebrew.”

“I’m one of four children who all had b’nei mitzvot in Israel, so my first experiences of Israel were those four family trips. And to me, the most amazing aspect of Israel was that it seemed to offer the possibility of time travel. The first time I went down that staircase in the Old City leading to the Cardo [a road in Jerusalem made of paving stones from the Roman era], when I was nine years old, my mind was blown by the sense that I had just traveled through time rather than space – and the visceral understanding that the street level, the time we’re in now, was literally built on these other layers from previous eras.”

“Then at 14, I took part in an event run by the Jewish community known as The Israel Contest. You had to read all these designated books about Israeli history and then there was this test, and the contestants with the highest scores would go to the Finals, and take part in an oral competition structured something like a game show.

I was the winner in my area, and the prize was a trip to Israel, but they’d clearly expected older teens to win the prize because I was too young for most of the trips they led. The only one that would take me at that time was March Of The Living, which also included a trip to Poland.

And this really marked the beginning of my People Love Dead Jews career. I mean, there was something so ironic about winning a contest based on my knowledge of Israel and the prize was a march from Auschwitz to Birkenau.”

“Another aspect of my Jewish education was created by my parents, who believed travel was an important part of learning Jewish history. So in 8th grade, we went to Spain and visited all these Jewish heritage sites. This was in 1992, so it was 500 years after the expulsion of Jews from the country. I always kept a journal on these trips – not about my personal feelings but more of a travelogue. I remember sharing that journal with my mother afterward, and she told me I should send it to Hadassah Magazine. Which I did, and they actually published it. This happened when I was only around 13 or 14. I believe the tagline of that piece was The Jews In Spain Are Mainly On The Plane, meaning the plane back to Newark Airport.

I kept a similar kind of journal on that March Of The Living trip, and since I already had my foot in the door at Hadassah Magazine, I sent that to them as well. And not only did they publish that piece too, but it was also nominated for a National Magazine Award, which made me the youngest person in history ever to be nominated for that award.”

“I spent two summers in Israel after that when I was still in high school.

During the first one, I went through this amazing program called the Alexander Muss High School in Israel. It’s a course in the history of Israel where you’re in a classroom learning a comprehensive account of Israeli history from ancient times until the present, but you’re also continually doing these field trips to the places where these things happened. So you end up seeing all the obligatory sites in Israel that you might see anyway if you just took a bus tour, but in this program you’re seeing them in chronological order. So at the beginning of the program, you’re going on archaeological digs and at the end, you’re visiting army bases and robotics factories. I ended up learning Israel’s history very well and really retaining it.

During the second summer, I went as part of a program called Bronfman Youth Fellowships in Israel. Every year they pick 26 students for this, from a variety of Jewish backgrounds. It’s an extensive study of Jewish texts from all these different perspectives. The idea of that program was to serve as a kind of incubator for future Jewish leaders.

This program was incredible — and just in my own cohort, there were so many people who went on to do very impressive things. Author Jonathan Safran Foer was one of them, and another was journalist Matti Friedman, who came from Toronto but then never left. There was Judy Batalion, who wrote The Light Of Days, about women resistance fighters during the Holocaust and also White Walls, a memoir about growing up as the child of Holocaust survivors. There was Rachel Gordon, a professor of Jewish Studies at the University of Florida, who recently published her first book, Postwar Stories, about using the power of middlebrow Jewish literature to re-brand Judaism as a religion in the U.S., which rendered it accessible and non-threatening to the American public. There was Itamar Moses who writes about Jewish themes for the stage and TV.

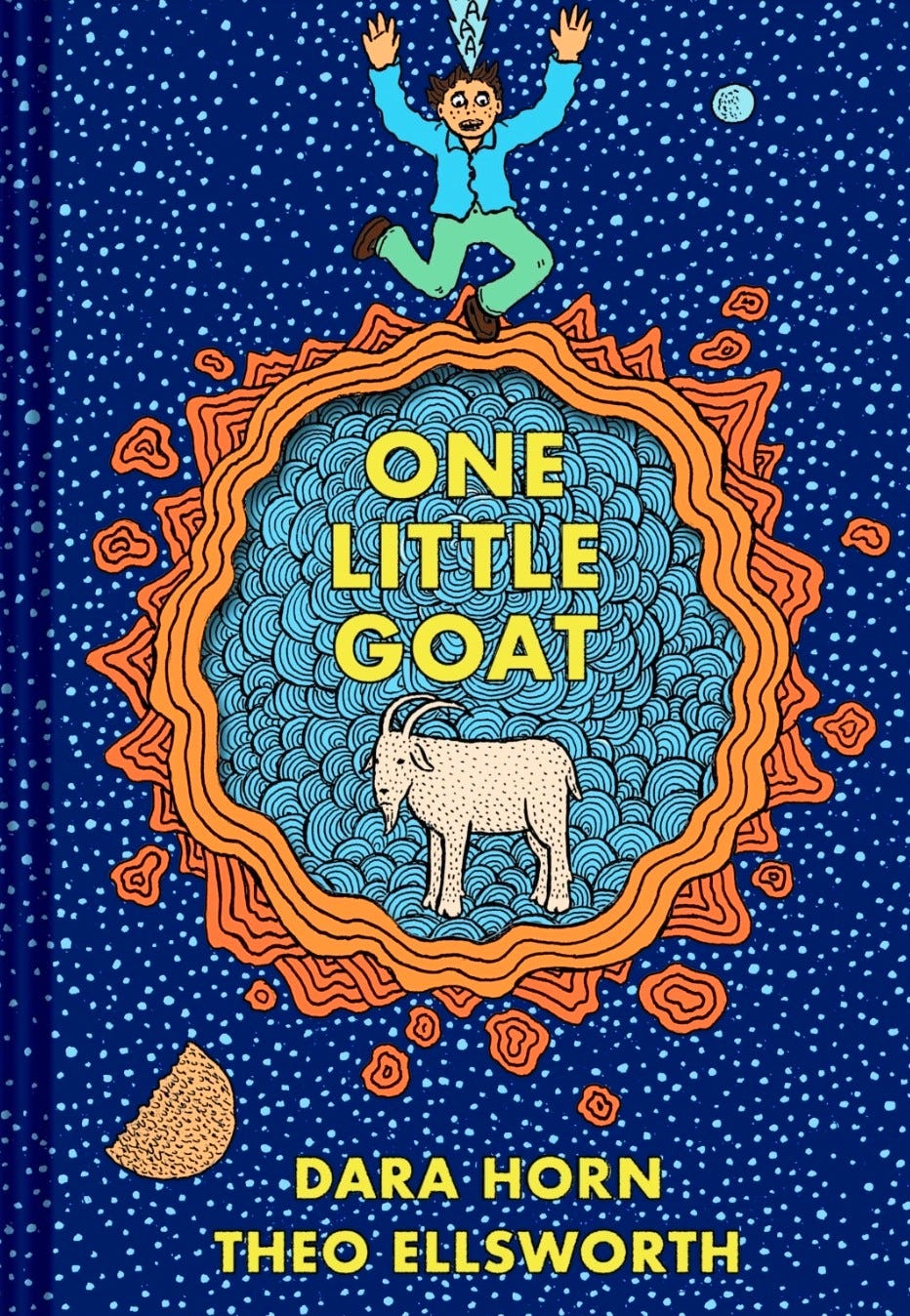

But beyond the extraordinary experience of being with all these people, the fellowship went beyond just this summer program in Israel. Because afterward, you also enter this alumni network of people in the classes ahead of you and behind you. One of whom is Lemony Snicket, who just gave me a hilarious blurb for my forthcoming graphic novel One Little Goat:

Here, at long last, is the time-traveling-goat-centric Passover adventure that my people have been awaiting for thousands of years.”

“I’m a Torah reader. I learned to read Torah at the age of 12 and then I had a job leading the junior congregation at my synagogue from 7th grade through high school, so I was reading Torah every week. My bat mitzvah parsha was Vayishlach, about Jacob and Esau, and in fact, I’ve since deepened my perspective on the wrestling match between Jacob and the other man, whom I feel is quite obviously Esau.

Jacob is a very interesting literary character to me, because he changes as a person. There’s a real character arc within his story. He starts out ripping off his brother, deceiving his blind father – it’s like, how low can you go, right? Lying to your blind father – that’s classy.

But he changes as things happen to him. So yes, he’s complicit in this sibling switch, but then he himself is victim to a sibling switch perpetrated by his father-in-law, right? With his wives. He lies to his father and then his sons lie to him, telling him that Jospeh was killed by a wild animal when they’d really sold him into slavery in Egypt.

People always say, later in his story, that Jacob wrestles with an angel. But I don’t believe it was an angel. First of all, several parshiyot back, he sees a band of angels going up and down a ladder in his dream, and the text is quite explicit about identifying them as angels. But in this story, it says: a man wrestled with him until daybreak. So the first piece of evidence is: it says a man; it doesn’t say an angel.

The second piece of evidence is: this is the night before he’s slated to meet Esau. His brother is coming to meet him with a security detail of around 400 men. And Jacob sends all these gifts to his brother ahead of his arrival.

But let’s glance at the backstory here for just a moment. The first time we ever meet these brothers, they’re wrestling within their mother’s womb. Rebecca is in misery, wanting to die, asking G-d why she’s still alive as she’s suffering so much from the epic battle inside her. And G-d tells her that two nations are wrestling within her womb, and the older shall serve the younger.

So I see the wrestling match before the brothers’ reunion later as the conclusion of this primordial wrestling match before birth.

Other interpretations posit that Jacob is wrestling with his own conscience, but I don’t buy that either. Jacob comes away from the match with a dislocated hip. When’s the last time a struggle with your conscience left you with a crippled hip?

Toward morning, the man tells Jacob: ‘Let me go, for dawn is breaking.’ Jacob replies that he won’t let the man go until the man blesses him. But instead of blessing him, the man tells him that going forward, Jacob’s name will now be Israel, which means Wrestles With G-d – ‘because you have struggled with G-d and man, and prevailed.’ The man then refuses to offer his own name, and departs.

Jacob names the place where this wrestling match unfolded Peni’el, which means the face of G-d, because – as he put it – ‘I have seen G-d face to face, and my life has been preserved.’

Jacob limps away to meet Esau with a new humility. Before this wrestling match, he likely would have found a way to avoid meeting the brother whose inheritance he stole years earlier. But now he bows to the ground seven times at Esau’s feet. Esau embraces him and the two brothers weep.

Then Jacob tells Esau: To see your face is to see the face of G-d.

In my interpretation, Jacob knows in that moment that the way we see G-d here on earth is by meeting the gazes of the people we’ve wronged, looking into their faces and knowing we can change.”

“I also teach the Joseph story when I teach Tanakh. The amazing thing to me about the Joseph story is what’s revealed when I have my students set up a decision tree, a way to game out what ultimately happens depending on how each event in the story unfolds.

So I list out all the events in the Joseph story. And something striking to notice is that G-d does not appear in this story. I think there’s a single line that tells us that G-d was with Joseph in the house of his Egyptian master. But other than that, there’s no dialogue with G-d. Many previous characters in the Torah -- like Abraham, Jacob, and Rebecca -- all do speak with G-d, but Joseph never has any interaction with G-d and G-d does not appear in the story in any explicit way.

But what’s really interesting to me comes at the end of the story, and to me, it’s the entire point. When Joseph reveals himself to his brothers, he tells them: “Don’t be sad or troubled that you sold me into slavery, because it was to save life that God sent me ahead of you.”

I think reading this, most of us have a tendency to go, Wait a minute, that’s a huge revision of history. Like: remember that heinous crime you committed against me? Well, hey, it’s all good, because it was just a benevolent act of G-d. I mean, as a reader, I think the impulse is to say: hold on, that’s not what happened.

But if you think about that interpretation as a choice Joseph is making in that moment, you realize he’s reinterpreting the actions of his family in a way that makes it possible for them to have a future together. He’s creating the conditions of a reconciliation, which is not all that different from what his father did in his final confrontation with Esau, when he tells him that seeing his face is like seeing the face of G-d.

But to the return to the decision tree: I have my students chart out each decision point on a board. So for instance:

Joseph’s brothers throw him in a pit. / They don’t throw him in a pit.

They sell him into slavery. / They don’t sell him into slavery.

After being propositioned by Potiphar’s wife, Joseph has an affair with her. / He rejects her advances.

And of course there’s many other interstitials in there, and what I do is: I have them plot it all out and find out what happens if any other course of action was taken at any one of those points. And what they very quickly discover is that if any alternative plot point had unfolded at any stage of the story, every single character would have ended up dead from the famine that Joseph averted.

And because Joseph is a kind of prophet, able to see the future in his dreams, he’s able to articulate that truth when he tells his brothers that G-d sent him into Egypt ahead of them in order to prevent that catastrophe. So you can see all the events in the story as having unfolded through human agency, but then you can also see the presence of God being brought to bear upon the story through human agency.

And the spiritual piece of the story for me is: that vision that Joseph has, which lets him see beyond what his brothers are able to see, is what enables him to build a future with them. And the meaning of that, to me, has to do with teshuvah, and the way we’re actually able to reinterpret the past. Because we can’t change the past, but we can change what it means to us.”

“When I’m lenying in a congregation – when I’m standing and chanting aloud from the Sefer Torah -- I feel that I’m present in the text. When I’m reading the Torah on the morning of Yom Kippur, I feel that it’s my responsibility as a Torah reader to bring the congregation into the text — and through my voice, I am bringing everyone there. The text is coming through me. Across thousands of years through me.

I am inside the text and I’m there with the people in the text. I’m there with Aharon HaKohen (Aaron the high priest) putting my hands on the scapegoat. I’m with him when he’s sending the goat out into the wilderness and then I’m following the goat into that wilderness. I’m there — and not just me, but I’m bringing everybody there. I’m activating the text — I feel that when I’m lenying.”

“For the past four years, I’ve been doing Daf Yomi, the literal translation of which is “a page a day”. This is a program that was started by a Polish rabbi in the 1920s. It’s a system where you study one page of Talmud every day until you finish the entire collection, which takes 7.5 years. And when I say a page of Talmud, that means 10 or 15 pages of dense material.

Often it’s really boring because certain parts are essentially legal case studies. Like right now, we’re looking at inheritance laws. But what’s interesting to me about it is that – well, first of all, just as when I read the Torah, I feel like I’m there with these sages trying really hard to parse things out. If you believe every word of the Torah is chosen and intentional, then every word is there instead of another word for a good reason, and we have to figure out: why this word instead of this other word? What is this word meant to teach us? If two phrases in succession are very similar, you have to wonder why it’s repeating itself, what nuances we’re meant to take from each iteration. And the answer is never that it’s bad editing and needlessly redundant; no, the second repetition is mean to impart something additional. It’s an exercise in close reading.

And studying the Talmud has made the parts of the Torah that used to feel boring to me — because they’re not part of a compelling narrative but all these technical details –- the parts of the Torah that, when we reached them in shul, I used to be like: oh my G-d, I’m so bored –- now, I’m like: whoa! I just spent a month studying, like, literally this one line. The whole last month of Daf Yomi was focused on this line. And seeing it in context is now a very different experience.

I don’t recommend Talmud study for people who aren’t really deep in the weeds, because that would be like trying to learn calculus without ever having studied algebra. But for me, it’s enhanced my relationship with the Torah.”

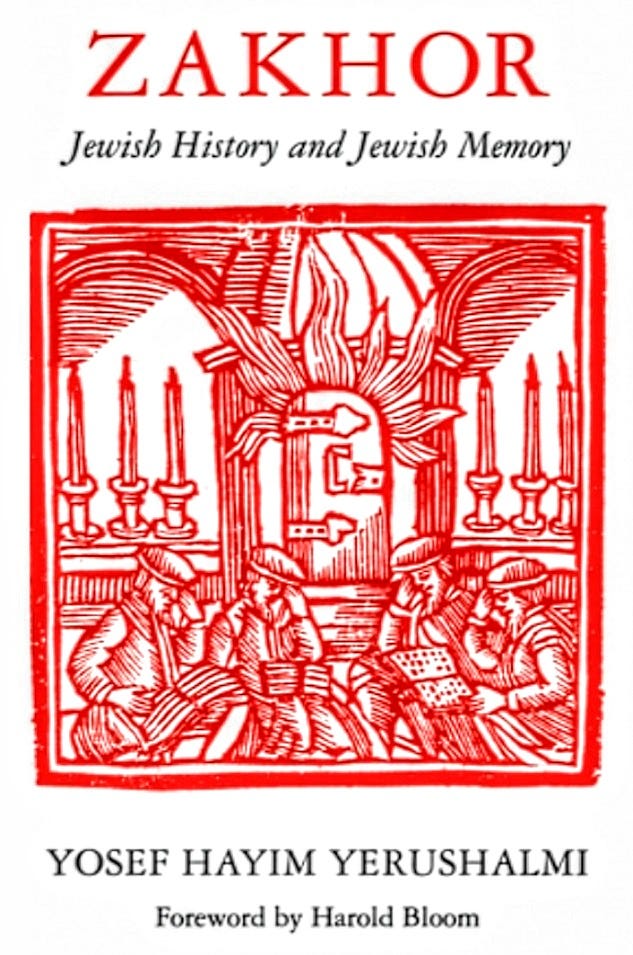

“I recommend a book by Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, which is Zakhor: Jewish History and Jewish Memory. It’s a slim book, only about 100 pages. Yerushalmi was a student of Salo Baron, a major 20th century historian who wrote a 21-volume history of the Jews.

In Zakhor, Yerushalmi talks about the fact that traditionally, Jews have less a sense of having a history and more a sense of having a memory. He distinguishes between these two. We don’t have a Greco-Roman tradition in which figures like Herodotus are writing history books. Josephus is the closest we have to this, but he’s only able to do it because he’s a Roman writing in Greek, and he’s also a traitor who leaves the Jewish people.

Yerushalmi says that in Jewish tradition, the past is not a series of events to be contemplated at a distance; it is a series of situations into which one is existentially drawn. As a historian, he was aware that the very nature of the historical project is at odds with the Jewish conception of time. For us, the past is still happening, and we’re not studying it so much as reliving it.

He illustrates what he means by asking us to think about the way we read and study the stories of our ancestors. Of course when we read the Torah story, we’re aware that Joseph died thousands of years ago.

But this week his brothers are selling him into slavery.

Next week he’ll be in prison.

And the week after that, he’ll be free.”

✡️

If you ever find her teaching a class we can take virtually, let me know. I’m all in.

What a fantastic read. Among others, I loved this part: "And the meaning of that, to me, has to do with teshuvah, the way we’re actually able to reinterpret the past. Because we can’t change the past, but we can change what it means to us.” So very true! And helpful! Also, I love that she is positive that Jacob fought his brother and not an angel. And the way she backed up her theory from evidence in the text. What a joy to read the entire essay! Thank you so much.