"How Far Would You Go To Give?"

Jews Of The Universe: Introducing Rabbi Dr. Shmuly Yanklowitz

“Nearly a decade ago, I donated my kidney to a complete stranger.

This journey began for me in very early adulthood, when I was volunteering in a small village in Ghana. By day, I was distraught and full of despair from seeing destitution and poverty at a level I had never witnessed before. But by night, I was full of hope from the smiles of children and from studying Torah sources and moral philosophers.

One of the thinkers who startled me, and opened my heart and mind, was Peter Singer, a radical utilitarian and moral philosopher at Princeton University. Singer essentially argues that when I buy a cup of coffee for $3, knowing that somebody will die tomorrow without a malaria net (that also costs $3), then in a sense, I have committed murder. Because I have chosen my luxury item over the value of another’s life.

He further argues that if I choose to keep a second kidney in my body – which could be viewed as a luxury organ, since most of us don’t need a second kidney – knowing that tomorrow, someone will die without getting a kidney, it is also akin to murder.

Now we can poke holes in his theories, as we should. But as a college kid, they split my heart wide open.”

“I started to ask myself: how much am I willing to sacrifice for my core beliefs? If I truly believe that every human being is created b’tzelem Elohim – in the image of G-d – with infinite dignity and worth, then how much am I willing to sacrifice for that conviction?

And so I left Ghana and continued my journey. I studied in various Yeshivot [Jewish study centers], went on to various grad school programs studying moral philosophers, founded two Jewish social justice organizations, married the love of my life, and had two children. But even with all this, I continued to feel that existential angst that was born for me in Ghana.

So I started to study the Jewish sources on the issue of organ donation. And I found that the Torah says: Lo ta’amod al dam re’echa: that we should not stand as bystanders beside the blood of our neighbors. And Ramban – Nachmanides, the great 13th-century philosopher and mystic from Spain – argues that essentially, we should be willing to give up all that we have to save the life of another. Because the Talmud says that to save one life is to save the world.”

“I also wanted to investigate the Jewish legal literature around the question of how much risk we should be willing to take –- because certainly self-protection is also of value. And when considering this question, our legal thinkers distinguish between vadai sakana and safek sakana: is something a definite risk, or a possible risk? And how, in moments of subjectivity, do we assess that risk to ourselves when giving to another?

But for me this wasn’t just an analytical, intellectual deliberation based on sources; it was also deeply spiritual and existential. Because the Talmud says that the first question asked at the Gates of Heaven is not: Did you maintain a strict adherence to kosher laws? or Did you keep Shabbat? No, as important as those may be, the first question asked of us will be: Did you live an ethical life? And the question that kept me up at night was: in my life, have I taken more or have I given more?

Now, I was sure – and I’m still sure – that if I were asked this question at the Gates of Heaven, my answer would be that I’ve taken far more than I’ve given. In our first few years of life, all our needs are fulfilled by other people. And then most of us go on to receive an education into our early twenties – just sitting there absorbing the knowledge that others are imparting to us. And then even beyond that, as a privileged American with a home, a car, a computer, a phone, healthcare… there’s no question that with all these needs met, I’m someone who has taken far more from the world than I’ve given.

And so I started to wonder: how can I change that equation? What would it look like to try to shift that imbalance in some small way? And this led me to look into the particular issue of organ donation, through the lens of halacha.”

“I found there were four primary concerns:

The first was emotional attachment to the body. Now, of course this is not only a Jewish concern, but a human concern. The idea of being cut into, even after our lives are over, and to have something taken out of us, or our loved ones – that feels daunting.

The second is superstition. One such superstition is called ayin hara – the evil eye – which has it that if I talk about my death, or I plan for my death, or if I compose a will, I might somehow be bringing death upon myself. Or if there’s a resurrection of the dead, I might be resurrected without all my organs.

The third is the treatment of the corpse. Jewish law has three prohibitions here. There’s nivul ha-met, forbidding any desecration of the body; halanat ha’met, forbidding delay in burying the body; and ha’anat ha’met, a prohibition against deriving any benefit from the corpse.

And finally, there’s the definition of death. There is controversy within Jewish law about whether death occurs with the cessation of a heartbeat, or with the death of the brain stem. But what if a medical team has their definition of death, and they take my organs before the threshold of death recognized by my own tradition? That would be problematic.

So all of these concerns have emotional and traditional weight. But my investigation into Jewish thought revealed that the value of pikuach nefesh – of saving a life – trumps all of those concerns.”

“Once it was clear to me that my tradition and my values not only supported, but in some sense perhaps even mandated, that I give the proposition of organ donation real consideration, I began to apprehend the crisis we’re facing in America today – which is that almost 90,000 Americans are waiting for a kidney.

Most people stay on that waiting list – in pain, in sickness, on dialysis -- for more than 5 years. And just last year, 3800 Americans died waiting for a kidney – just in the U.S., not even to mention the rest of the world. So I started to wonder: if the crisis has gotten to this point, then what would our dream look like? Wouldn’t it be that no person should needlessly die? How could we construct a society where we could incentivize and inspire others to save every such life?

And so I began to think about this more deeply and I approached my #1 team about the issue.

Now, my kids were an easy sell; they just got a cookie. My wife and I had a longer conversation.”

“But I got my whole family on board. My rabbis, my colleagues, my friends: they all got on board with me. Of course there were concerns and questions about safety and risk, but they ultimately saw that I had investigated this issue fully and that I was committed. And they supported the plan, which meant the world to me.

Once my family was on board, I contacted an organization called Renewal. Renewal is a Jewish organization that holds the hands of those who want to become living donors.

They suggested a match of a young man who was orphaned at the age of 2. I immediately said he was the right person. They could have suggested anyone.

I moved forward with the process – with fear, because I’d never had any surgery in my life, let alone major surgery. But with my team on board, and having thoroughly investigated the issue, I decided to commit to it.

The morning of the surgery was the first time I met the recipient. It was one of the most emotional moments of my life, and it was captured on video [below].”

“Just a short time after I met the recipient, they brought us both into surgery. I got four laproscopic incisions on my left side, and another larger incision beneath them where they took the kidney from my body and placed it into his, making us like blood brothers.

A few hours later, we were out of surgery. It took me a few weeks to recover to 100%. The truth is that my wife did all the hard work; she cared for the kids and for me while I took it easy for a few weeks. And my recipient, thank G-d, is doing very well and thriving in his life back in Israel.”

“So with that, I once again gained more than I gave. Because I gained not only a new friend, but a new perspective on life: this sense that our bodies are so temporal; they will pass in no time. But our souls are eternal.

Our organs will die with our bodies, but if we give them away, they become eternal. They continue to give the gift of life.

And I believe the Jewish community can do more to show global leadership. Whether it’s contacting Renewal to become a living donor, contacting the Halachic Organ Donor Society to become a donor after life, having conversations with our families, signing our wills, checking the box on our driver’s license – we can clarify to our loved ones and others that we want to give the gift of life.”

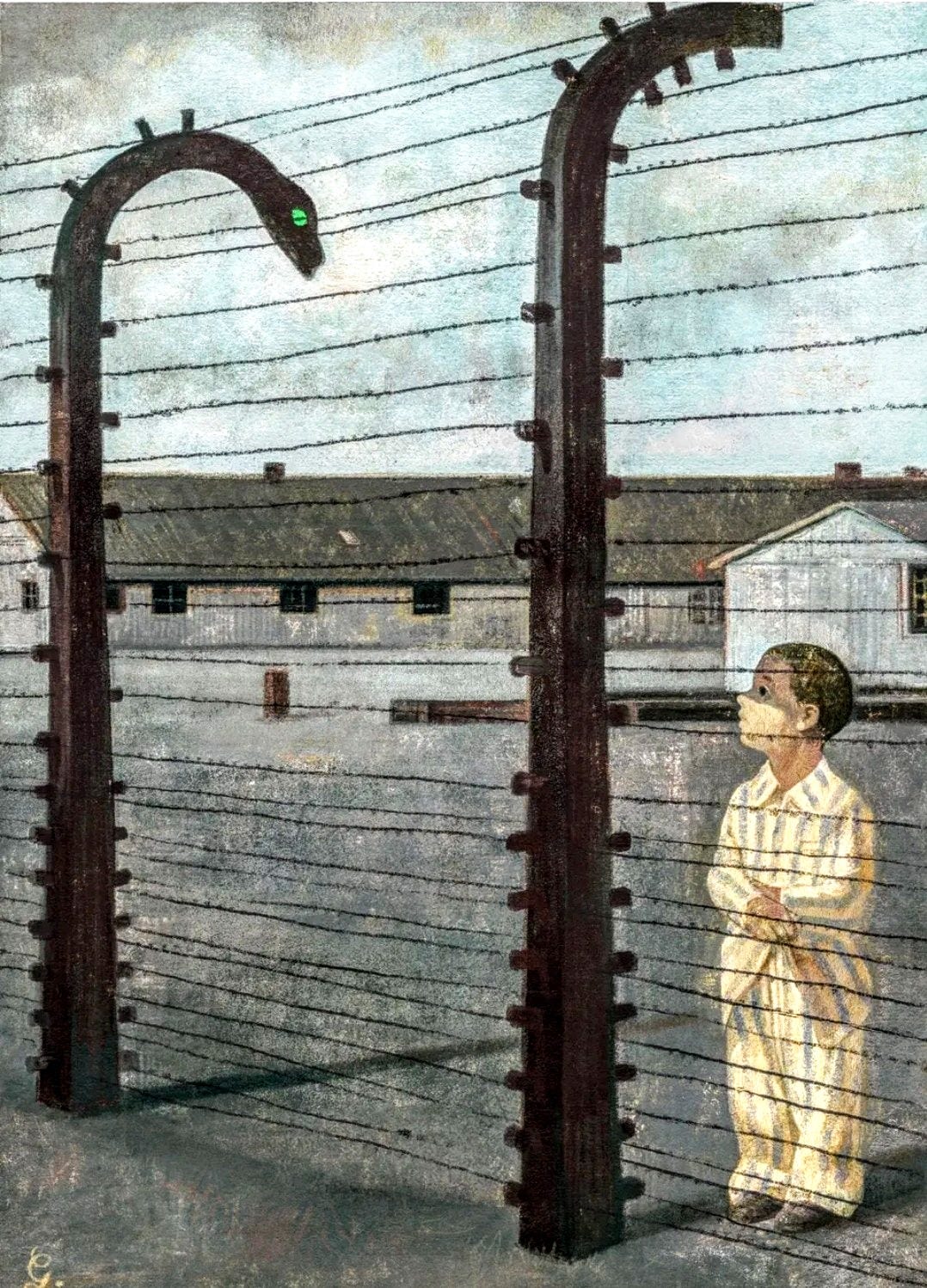

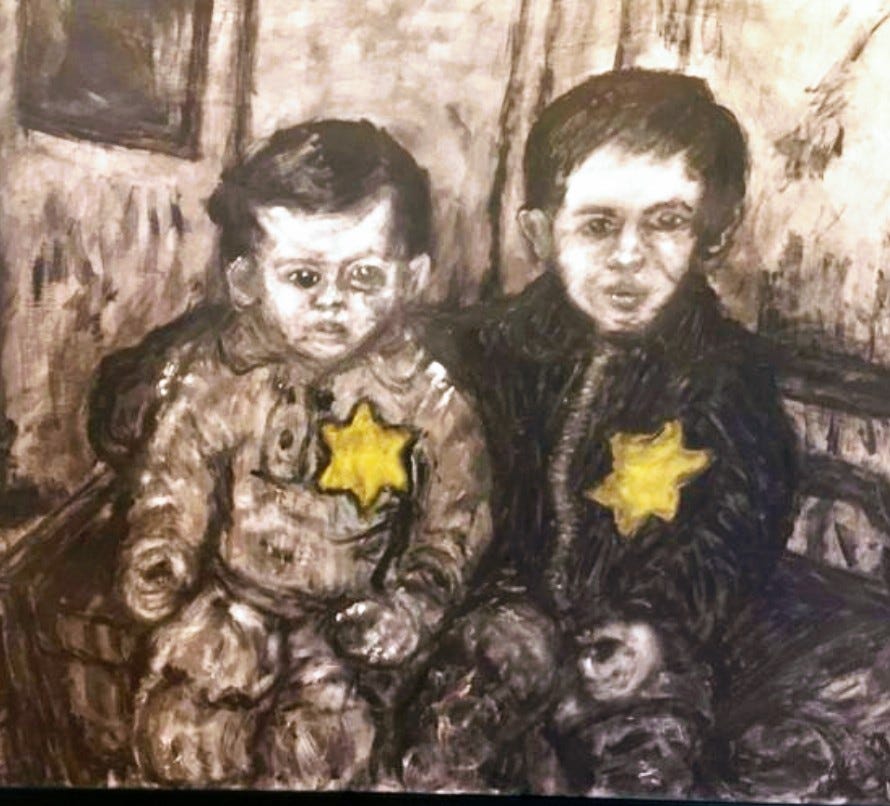

“And I want to end with this true story:

A Holocaust survivor had a son who was dying of kidney failure. He was very sick for many years and they couldn’t find anyone who was a medical match and willing to donate.

And then finally, they got a call about a matching donor.

They flew immediately to Toronto to meet the donor and his family and the medical team. But then the doctor came into the room and said, “I’m so sorry, but it’s off. The family has decided they won’t donate to you.”

The survivor was aghast. “What? How can this be? This is my only child. I’m a Holocaust survivor. Please, if only they’ll reconsider, I’ll do anything!”

Again the doctor said he was so sorry, but the other family’s decision was final.

The survivor found the address of the cancelled donor’s father and went to his house. The man came to the door and told him to leave. “My decision is final – get off my property!”

The father of the dying boy said once more: “Please, I’m a Holocaust survivor. This is my only son. I’ll do anything for your son, who matched him, if only he’ll donate to mine!”

The man in the doorway said: You really don’t recognize me?

You don’t recognize me from Auschwitz?

The Nazis told you to murder my son.

And you did!

So get off my property right now and don’t ever let me see you again.”

“The survivor stared at the man in the doorway and his eyes filled with tears.

That was you? he asked hoarsely.

But I never killed your son.

I hid him away -- and I raised him as my own.

So the boy who needs a kidney? He’s your son.

And your other son is a match for him because they’re brothers.”

“Friends, sometimes when we give the gift of life, we receive miraculous gifts in return. Organ donation is not only a mitzvah; it is central to our Jewish mission and our way of life. May we all find our path. G-d bless you.”

✡️

To learn more about Rabbi Dr. Shmuly Yanklowitz, you may visit his website here:

https://www.rabbishmuly.com/

.